Today in this article we will discuss about the Top 10 Renewable and Non-Renewable Sources of Energy with PDF, PPT and Infographic so, Let’s Discover the top 10 renewable and non-renewable sources of energy – explained with real facts, expert insights, pros, cons, and their role in shaping a sustainable future. This complete 2025 guide covers solar, wind, hydro, geothermal, tidal, wave, biomass, coal, oil, natural gas, nuclear, and more. Perfect for students, researchers, and eco-conscious readers.

Think about the last 24 hours of your life. You woke up to an alarm powered by electricity, made coffee on a gas or electric stove, commuted using fuel, and spent the day in a heated or cooled building. Every single one of those actions consumed energy – and the source of that energy matters more today than at any other point in human history. We are living through one of the most consequential energies transitions the world has ever seen. The choices made in the next decade about which energy systems to build, fund, and retire will shape global temperatures, economic stability, and the quality of life for billions of people over the coming century. At the center of it all is a fundamental distinction: renewable vs. non-renewable energy. In this comprehensive guide, we cover the top 10 renewable sources and the top 10 non-renewable sources of energy – what they are, how they work, their advantages and disadvantages, real-world data, and what it all means for the future of our planet.

What Is an Energy Source? Understanding the Basics

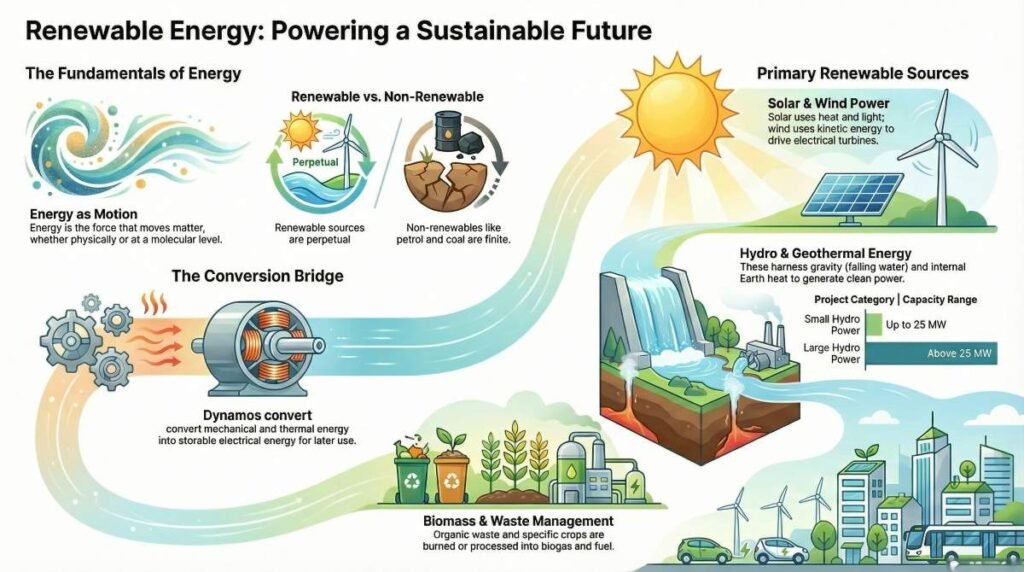

An energy source is any material, phenomenon, or process from which useful energy can be extracted – whether to generate electricity, heat buildings, power vehicles, or run industry. All practical energy sources on Earth trace back to just two origins: the Sun and the radioactive decay within the Earth’s core.

Energy sources are divided into two broad categories based on one critical question: Can this resource replenish itself on a human timescale?

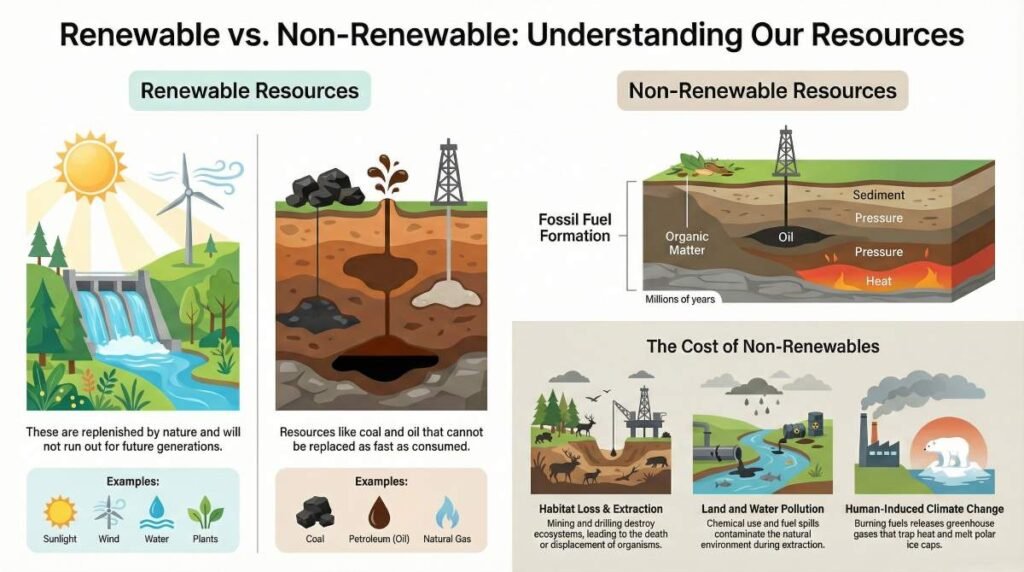

Renewable energy sources are those that naturally replenish within a human lifetime – sunlight, wind, flowing water, and geothermal heat are continuously available and will not run out. Non-renewable energy sources are those that exist in finite quantities and take millions of years to form – primarily fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas. Once consumed, they cannot be meaningfully replaced.

This distinction is not merely scientific. It has profound economic, environmental, and geopolitical consequences that shape global policy decisions every single day.

Top 10 Renewable and Non-Renewable Sources of Energy PDF | PPT SLIDES

Top 10 Renewable Sources of Energy

Renewable energy is no longer a niche experiment. As of 2025, renewables supply over 30% of global electricity and are the cheapest new source of power in most countries. Here are the top 10 renewable energy sources, explored in depth.

#1. Solar Energy

Solar energy is arguably the most transformative energy technology of the 21st century. It harnesses electromagnetic radiation from the Sun using photovoltaic (PV) panels – which convert sunlight directly into electricity – or concentrated solar power (CSP) systems, which use mirrors to focus sunlight and generate heat for turbines.

The numbers are staggering: more energy strikes the Earth from the Sun in 90 minutes than the entire human civilisation consumes in a year. And the technology to capture it has become dramatically cheaper. Solar PV module costs have fallen by over 99% since 1976, making solar the cheapest source of electricity ever recorded in history, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Global installed solar capacity surpassed 1.6 terawatts (TW) in 2024. Rooftop solar systems can reduce household electricity bills by 50 to 90 percent. Modern bifacial panels even capture diffused light on cloudy days. And agrivoltaic systems – where solar panels are installed above farmland – allow dual use of land for energy and food production simultaneously. Solar produces zero noise, zero emissions, and zero water consumption during operation.

#2. Wind Energy

Wind energy converts the kinetic energy of moving air masses into electricity through wind turbines. It is one of the fastest-growing and most cost-effective energy technologies on Earth. Onshore wind farms are now cheaper to build and operate than almost any other energy source in most countries. Offshore wind farms, located out at sea where winds are stronger and more consistent, are unlocking enormous untapped potential in coastal nations.

Over 2,100 gigawatts (GW) of wind capacity is installed worldwide as of 2025. A single large offshore turbine rated at 15 MW can power approximately 15,000 homes. Wind turbines have a lifespan of 25 to 30 years and require relatively low ongoing maintenance. Wind power consumes zero water during operation – a critical advantage in water-stressed regions. Countries like Denmark regularly generate over 100 percent of their electricity needs from wind alone on high-wind days. Wind energy also creates roughly three times more jobs per unit of energy than the coal industry.

#3. Hydropower

Hydropower is the world’s oldest and most widely deployed renewable energy source. It harnesses the gravitational energy of flowing or falling water to spin turbines and generate electricity. From massive mega-dams like the Three Gorges Dam in China to small run-of-river micro-hydro systems serving remote villages, hydropower is extraordinarily versatile.

Hydroelectric generation currently provides approximately 16 to 17 percent of global electricity – making it the single largest renewable source by volume. Unlike solar and wind, hydroelectric plants can ramp output up and down within minutes, making them invaluable for grid stability. Pumped-hydro storage – where water is pumped uphill when electricity is cheap and released downhill to generate power when needed – accounts for over 90 percent of all grid-scale energy storage globally. Many hydroelectric plants built in the 1930s are still operating today, with lifespans routinely exceeding 80 to 100 years.

#4. Geothermal Energy

Geothermal energy taps the vast heat generated within the Earth’s interior – a product of planetary formation and the ongoing radioactive decay of minerals deep underground. It can be used directly for space heating and industrial processes, or converted into electricity via steam-driven turbines. Unlike solar and wind, geothermal is not dependent on weather or time of day.

Iceland is the world’s most prominent example: the country generates nearly 30 percent of its electricity and approximately 90 percent of its space heating from geothermal sources. Geothermal power plants have a capacity factor of over 90 percent – meaning they produce electricity almost continuously – compared to around 25 percent for solar and 35 percent for wind. Kenya generates over 40 percent of its electricity from geothermal energy, demonstrating its viability for developing nations. Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS), still under development, could eventually access geothermal heat almost anywhere on Earth, dramatically expanding the technology’s reach.

#5. Biomass Energy

Biomass energy is derived from organic materials – agricultural residues, wood pellets, dedicated energy crops like switchgrass, animal manure, and municipal solid waste. It is one of the only renewable sources that can be converted directly into liquid fuels, making it essential for decarbonising transportation sectors that are difficult to electrify, such as aviation and shipping.

Biomass currently provides approximately 10 percent of global total energy – the largest share of any renewable source in overall energy terms (not just electricity). Biogas produced from decomposing organic waste can replace natural gas in existing pipelines with no infrastructure modifications. Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) derived from biomass is already being used on commercial flights. The concept of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) – burning biomass for energy while capturing the CO2 emissions – could theoretically achieve net negative carbon emissions.

#6. Tidal Energy

Tidal energy harnesses the gravitational forces of the Moon and Sun on Earth’s oceans, which create the rhythmic rise and fall of sea levels we call tides. These forces are so predictable that tidal patterns can be forecast centuries in advance, making tidal energy unique among renewables for its near-perfect reliability.

Tidal barrages, like the La Rance facility in France (operational since 1966), dam tidal estuaries to capture energy as water flows in and out. Tidal stream generators – which resemble underwater wind turbines – are placed in fast-moving tidal channels and generate power from the flow of water rather than its height. Because water is 832 times denser than air, even slow-moving tidal currents contain enormous amounts of energy. The UK has some of the best tidal resources in the world, particularly in the Severn Estuary and around the Orkney Islands. Global tidal energy potential is estimated at over 800 terawatt-hours (TWh) per year.

#7. Wave Energy

Wave energy captures the kinetic and potential energy stored in ocean surface waves – generated by wind blowing across open water over long distances. It represents one of the most abundant and least exploited renewable energy resources on Earth, with particular promise for coastal nations at higher latitudes where wind-driven waves are most powerful.

The global theoretical wave energy potential exceeds 2,000 TWh per year. Wave energy converters (WECs) come in many forms – floating devices that bob with waves, oscillating water columns, and submerged pressure differentials – all designed to extract mechanical energy from wave motion and convert it into electricity. Portugal, Scotland, Australia, and Japan are among the global leaders in wave energy research and development. A key advantage of wave energy over solar and wind is greater consistency along coastlines, since waves continue to arrive even after local winds have died down.

#8. Green Hydrogen

Green hydrogen is produced by using renewable electricity to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen through a process called electrolysis – generating zero carbon emissions in the process. Unlike electricity, hydrogen can be stored for extended periods, transported through pipelines, and used in a wide range of applications far beyond electricity generation, including heavy industry, long-haul transport, and seasonal energy storage.

The significance of green hydrogen lies in its ability to solve one of the hardest problems in the energy transition: how to decarbonise sectors like steel manufacturing, cement production, shipping, and aviation that cannot easily run on direct electricity. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles emit only water vapour. Green hydrogen can be blended with natural gas in existing pipelines at up to 20 percent concentration without infrastructure changes. The cost of green hydrogen is falling rapidly and is projected to reach around $1 per kilogram by 2030 in optimal locations, making it increasingly competitive with fossil-based alternatives.

#9. Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC)

Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion exploits the natural temperature difference between warm tropical surface seawater and cold deep ocean water to run a heat engine and generate electricity. In tropical regions, this temperature differential typically exceeds 20 degrees Celsius – enough to drive turbines in a continuous, weather-independent cycle.

OTEC is particularly relevant for tropical island nations – many of which currently rely on expensive imported diesel for electricity. Because ocean temperature gradients change very slowly and predictably, OTEC can operate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year with no fuel input. Beyond electricity, OTEC systems pump cold deep seawater to the surface as a byproduct, enabling low-energy air conditioning, aquaculture, and freshwater desalination. Japan and Hawaii have operated OTEC pilot plants since the 1980s. The global theoretical potential of OTEC is estimated in the hundreds of terawatt-hours per year from tropical ocean regions alone.

#10. Emerging Renewables – Piezoelectric, Salinity Gradient, and Radiative Cooling

A new frontier of emerging renewable technologies is beginning to complement the mainstream sources. Piezoelectric energy harvesting converts mechanical stress – from footsteps, vehicle vibrations, or structural movement – into small amounts of electricity, with applications in smart sensors, wearables, and urban infrastructure. Salinity gradient energy (also called osmotic power or blue energy) exploits the chemical potential difference where freshwater rivers meet saltwater seas, generating power through controlled osmosis across specialised membranes.

The Netherlands opened the world’s first salinity gradient power plant in 2014, demonstrating real-world feasibility. Radiative cooling – a passive technology that exploits the Earth’s ability to radiate heat into outer space at night – can reduce building temperatures without any electricity consumption, and newer systems are being developed to extract small amounts of usable power from the temperature differential. The global theoretical potential of salinity gradient alone is estimated at 1,700 TWh per year. While these technologies are still far from mainstream commercialisation, they represent the next wave of renewable innovation.

Top 10 Non-Renewable Sources of Energy

Non-renewable energy sources still power approximately 80 percent of total global energy consumption as of 2025. Understanding these sources – their value, their environmental costs, and their long-term trajectories – is essential to forming a complete picture of the world’s energy system.

#1. Coal

Coal is a solid fossil fuel formed over approximately 300 million years from the compressed remains of ancient plant matter. It powered the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries, and it remains a dominant source of electricity worldwide – particularly in China, India, and Southeast Asia. It is also the single largest contributor to human-caused climate change of any energy source.

Coal currently supplies approximately 36 percent of global electricity generation. It is the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, producing around 1 kilogram of CO2 per kilowatt-hour generated. There are three main types: lignite (the softest and most polluting), bituminous (the most widely used), and anthracite (the hardest and cleanest-burning variety). Beyond CO2, coal combustion releases sulfur dioxide (causing acid rain), nitrogen oxides (contributing to smog), mercury (a neurotoxin), and fine particulate matter that causes respiratory disease. Air pollution from coal is estimated to cause approximately 800,000 premature deaths per year globally. Many nations have committed to coal phase-outs – the United Kingdom fully ended coal power generation in September 2024.

#2. Crude Oil (Petroleum)

Crude oil is a liquid fossil fuel found in underground reservoirs, formed from the compressed remains of ancient marine organisms over tens of millions of years. After extraction, it is refined into a vast range of products: gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, heating oil, lubricants, and petrochemicals that underpin modern plastics, pharmaceuticals, fertilisers, and synthetic textiles.

Global oil consumption reached a record high of approximately 102 million barrels per day in 2024. Oil powers around 92 percent of all global transportation – road vehicles, aircraft, and ships alike. Proven global oil reserves are estimated to last roughly 50 more years at current consumption rates, though that figure shifts constantly with new discoveries and changing demand. Oil spills – from events like the Exxon Valdez in 1989 and the Deepwater Horizon blowout in 2010 – cause devastating and long-lasting ecological destruction to marine and coastal ecosystems. Petrochemicals derived from crude oil are present in over 6,000 everyday products, meaning oil’s role extends far beyond transportation and energy.

#3. Natural Gas

Natural gas, composed primarily of methane, is the cleanest-burning of the three major fossil fuels. It produces roughly 50 percent less CO2 than coal and around 30 percent less than oil per unit of energy generated, which is why it has been widely promoted as a ‘transition fuel’ – a bridge between coal-heavy grids and fully renewable systems. It is used for electricity generation, space heating, industrial processes, and cooking in hundreds of millions of homes worldwide.

Natural gas provides approximately 23 percent of global electricity and 22 percent of total global energy. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) – cooled to minus 162 degrees Celsius for shipment – has transformed global gas trade, allowing gas to be exported by tanker to countries without pipeline connections. However, methane leaks during extraction, processing, and transport (known as fugitive emissions) significantly erode the climate advantage of natural gas over coal, since methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than CO2 over short timescales. The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine exposed the dangerous degree to which European nations had become dependent on Russian gas, triggering an energy crisis and accelerating renewable investment across the continent.

#4. Nuclear Energy (Uranium Fission)

Nuclear power generates electricity through the controlled fission of uranium-235 atoms inside a nuclear reactor. The process releases enormous amounts of heat, which boils water into steam to drive turbines. Unlike fossil fuels, nuclear reactors produce virtually zero CO2 during operation, placing nuclear among the lowest-carbon electricity sources available at scale.

There are approximately 440 operating nuclear reactors worldwide, providing about 10 percent of global electricity. France generates over 70 percent of its electricity from nuclear power – the highest share of any nation. Nuclear power has a very high energy density: a single uranium fuel pellet the size of a fingertip contains as much energy as 17,000 cubic feet of natural gas. Over its full lifecycle, nuclear energy emits approximately 12 grams of CO2 per kilowatt-hour – comparable to wind and solar. Key challenges include the high upfront capital cost of construction, the management and long-term storage of radioactive waste, and public concerns about accident risk following events like Chernobyl (1986) and Fukushima (2011). Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), currently under development, aim to address cost and flexibility concerns.

#5. Oil Shale

Oil shale is a type of sedimentary rock containing a solid organic compound called kerogen, which can be converted into a synthetic oil when heated to high temperatures. Unlike conventional crude oil, oil shale cannot simply be pumped out of the ground – it requires mining and thermal processing before it becomes usable fuel, making it significantly more energy-intensive and expensive to produce.

The United States holds the largest known oil shale reserves in the world, estimated at approximately 2 trillion barrels – a figure that dwarfs all known conventional oil reserves globally. However, the high water consumption, significant land disturbance from surface mining, and relatively low net energy return on investment have prevented large-scale commercialisation. Estonia is a notable exception: it generates approximately 75 percent of its electricity from oil shale, a unique dependency that reflects its lack of domestic alternatives. In-situ conversion processes, which heat oil shale underground without mining it, are under development as a lower-impact alternative.

#6. Tar Sands (Oil Sands)

Tar sands, also known as oil sands, are a mixture of sand, clay, water, and a thick, viscous form of oil called bitumen. They are found primarily in the Athabasca region of Alberta, Canada, and in the Orinoco Belt of Venezuela. Extracting usable oil from tar sands involves either surface strip-mining followed by hot water separation, or injecting steam deep underground to soften the bitumen so it can be pumped out – a process called Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD).

Canada’s Alberta oil sands contain approximately 165 billion barrels of proven recoverable reserves, making Canada the holder of the world’s third-largest oil reserves. However, producing a barrel of oil from tar sands generates roughly three times the greenhouse gas emissions of conventional oil extraction. Surface mining operations have disturbed over 900 square kilometres of Canadian boreal forest – one of the world’s most important carbon sinks and biodiversity habitats. The industry employs over 150,000 Canadians, creating significant political and economic complexity around any transition away from the resource.

#7. Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG / Propane)

Liquefied petroleum gas is a mixture of propane and butane – hydrocarbon gases produced as byproducts of natural gas processing and crude oil refining. At normal temperatures and pressures, these gases are vaporous; they are compressed into liquid form for easy storage and transportation in cylinders and tanks. LPG is widely used for cooking, space heating, agricultural crop drying, and as vehicle fuel (where it is called autogas).

LPG is particularly important in rural and developing regions where natural gas pipelines do not reach. Over one billion people worldwide use LPG cylinders for cooking – especially across sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. Compared to burning wood, charcoal, or dung (which is how approximately 2.3 billion people still cook), LPG produces dramatically less indoor air pollution, offering significant public health benefits. Global LPG demand exceeded 320 million tonnes in 2023. As a vehicle fuel, autogas produces 10 to 15 percent less CO2 than petrol and significantly lower particulate emissions.

#8. Peat

Peat is a soft, spongy organic material formed from the partial decomposition of plant matter in waterlogged, low-oxygen conditions such as bogs and fens. It accumulates extremely slowly – at roughly 1 millimetre per year – meaning peat deposits that are metres deep took thousands of years to form. Though technically organic and derived from plants, peat is considered functionally non-renewable because its formation rate is far too slow to replace what is extracted.

Peat has been burned for domestic heating and electricity generation for centuries, particularly in Ireland, Finland, Scotland, and Russia. Ireland officially ended peat-fired electricity generation in 2020, transitioning instead to wind power and natural gas. The ecological significance of peatlands far exceeds their energy value: though peatlands cover only around 3 percent of Earth’s land surface, they store approximately twice as much carbon as all of the world’s forests combined. When peatlands are drained and burned, they release centuries of accumulated carbon rapidly. Protecting and restoring peatlands is now recognised as one of the most cost-effective climate mitigation strategies available.

#9. Methane Hydrates (Gas Hydrates)

Methane hydrates are ice-like crystalline structures in which methane molecules are trapped within a lattice of water molecules. They form under conditions of high pressure and low temperature – primarily in deepwater ocean sediments and in permafrost regions at high latitudes. Methane hydrates are extraordinary in their scale: conservative estimates suggest they contain more natural gas than all known conventional fossil fuel reserves combined.

Japan, China, India, and the United States are all conducting active research and development programmes to extract methane from hydrate deposits. Japan achieved the first offshore methane hydrate production test in 2013 in the Nankai Trough. However, commercial extraction remains technically extremely challenging and economically unviable – most analysts estimate it is still 10 to 20 years from large-scale use. There is also a significant environmental risk dimension: the destabilisation of seafloor methane hydrates due to ocean warming is being closely monitored, since uncontrolled release of large quantities of methane into the atmosphere would dramatically accelerate global warming.

#10. Thorium (Advanced Nuclear Fuel)

Thorium is a naturally occurring, mildly radioactive metallic element that can be used as a nuclear fuel in advanced reactor designs. It is 3 to 4 times more abundant in the Earth’s crust than uranium, found in greater geographic distribution, and produces significantly less long-lived radioactive waste when used as reactor fuel. Crucially, thorium cannot on its own sustain a nuclear chain reaction – it must first be irradiated to convert it into fissile uranium-233 – making thorium-based reactors inherently proliferation-resistant.

India has the world’s largest thorium reserves and has built a three-stage national nuclear programme with thorium at its core, targeting commercial thorium reactors by the 2040s. China has invested billions of dollars into a Molten Salt Reactor (MSR) programme using thorium and is targeting demonstration plants by the 2030s. A single tonne of thorium, when fully used in an efficient reactor, could theoretically power a 1,000 MW plant for an entire year. MSRs using thorium could even be designed to run on existing nuclear waste – addressing the radioactive waste problem and generating energy simultaneously. Thorium represents the most promising next-generation nuclear fuel option and may play a significant role in long-term low-carbon energy supply.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Renewable Energy

Advantages

- Environmentally clean – produces little to no greenhouse gas emissions during operation

- Inexhaustible supply – solar, wind, and water will never run out on any human timescale

- Falling costs – solar and wind are now the cheapest electricity sources in history

- Energy independence – nations can generate power domestically, reducing import vulnerability

- Job creation – the renewable energy sector employed 13.7 million people globally in 2023

- Improved public health – cleaner air from reduced combustion significantly reduces disease

- Distributed generation – small-scale systems can power individual homes and communities

- Water conservation – most renewable technologies consume far less water than fossil fuel plants

Disadvantages

- Intermittency – solar and wind do not produce power 24 hours a day, every day

- Energy storage challenges – storing large amounts of electricity in batteries remains costly

- High upfront costs – initial infrastructure investment can be substantial despite low operating costs

- Land use – large solar and wind farms require significant amounts of land

- Location dependency – not all renewable technologies are viable in all geographies

- Grid integration complexity – variable output requires sophisticated grid management

- Supply chain concerns – manufacturing solar panels and wind turbines requires critical minerals

Also read: Top 30 Most Important Revolutions in History (World) .PPTX

Advantages and Disadvantages of Non-Renewable Energy

Advantages

- Very high energy density – fossil fuels pack enormous energy into a small, transportable volume

- Reliability – can generate power on demand regardless of weather or time of day

- Established infrastructure – decades of investment in pipelines, refineries, and power stations

- Versatility – fossil fuels underpin thousands of products beyond just energy

- Lower short-term cost in many regions – where infrastructure already exists, costs can be low

Disadvantages

- Finite supply – all fossil fuels will eventually run out, with oil reserves lasting roughly 50 more years

- Climate change – burning fossil fuels is the primary driver of global warming and extreme weather

- Air and water pollution – extraction, refining, and combustion pollute ecosystems and communities

- Public health damage – fossil fuel pollution causes an estimated 8 million premature deaths per year

- Price volatility – oil and gas prices fluctuate dramatically, creating economic instability

- Energy insecurity – countries reliant on fossil fuel imports are vulnerable to supply disruptions

- Environmental destruction – mining and drilling cause significant habitat loss and contamination

Renewable vs. Non-Renewable Energy: Key Differences

- Supply: Renewable energy replenishes naturally and is effectively inexhaustible; non-renewable energy is finite and cannot be replaced on any practical human timescale.

- Carbon emissions: Renewable energy produces zero or near-zero CO2 during operation; fossil fuels release large amounts of CO2 and other greenhouse gases every time they are burned.

- Environmental impact: Renewable energy has a generally low environmental impact during operation; fossil fuel extraction and combustion causes air pollution, water contamination, and habitat destruction at scale.

- Reliability: Fossil fuel plants can generate power on demand at any hour; solar and wind are weather-dependent, though energy storage and grid management solutions are rapidly improving.

- Cost trends: Renewable energy costs have fallen dramatically and continue to decline; fossil fuel prices are volatile and subject to geopolitical shocks.

- Energy security: Renewables allow domestic energy production, reducing dependence on imports; fossil fuel dependence creates vulnerability to supply disruptions and price manipulation.

- Public health: Renewable energy improves air quality and public health; fossil fuel combustion causes millions of preventable deaths annually from air pollution.

- Long-term viability: Renewable energy is indefinitely sustainable; non-renewable energy will eventually run out.

The Environmental Impact of Energy Choices

Climate Change and Carbon Emissions

Since the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 1750s, burning coal, oil, and natural gas has increased the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere from 280 parts per million to over 422 ppm in 2024. This has driven approximately 1.2 degrees Celsius of global average warming – with consequences already visible in the form of rising sea levels, melting glaciers, intensifying storms, prolonged droughts, and shifting agricultural zones.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states clearly that to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius – the threshold beyond which climate impacts become significantly more severe – global CO2 emissions must reach net-zero by around 2050. That requires almost entirely replacing unabated fossil fuels with clean energy alternatives within a single generation.

Looking at lifecycle carbon emissions per kilowatt-hour, the contrast is stark. Coal generates around 820 grams of CO2-equivalent per kWh. Natural gas generates approximately 490 g/kWh. In contrast, wind energy produces around 11 g/kWh, nuclear approximately 12 g/kWh, hydropower around 24 g/kWh, and solar PV approximately 48 g/kWh. Switching from coal to renewables is one of the single most impactful climate actions possible.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health

Beyond climate, energy extraction profoundly affects biodiversity. Coal strip mining eliminates entire ecosystems – forests, wetlands, and hillsides are razed to reach seams below. Oil spills cause devastating ecological harm: the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster killed hundreds of thousands of birds and marine mammals and left lasting contamination along hundreds of miles of Alaskan coastline. Natural gas hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has been linked to groundwater contamination, induced seismicity, and habitat fragmentation in multiple regions.

Renewable energy is not entirely without impact. Large hydroelectric dams alter river ecosystems, block fish migration routes, and have historically displaced large numbers of local communities. Solar farms change land use and can affect local plant and animal life. Wind turbines occasionally harm birds and bats. However, the scale and severity of ecological damage from renewables is generally orders of magnitude smaller than that caused by fossil fuel extraction and combustion.

Air Quality and Public Health

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 7 million people die prematurely each year from air pollution – the overwhelming majority from fossil fuel combustion. Coal-fired power plants emit sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, mercury, and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) that penetrates deep into lungs and bloodstream, causing respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Transitioning to clean energy is not only an environmental strategy – it is one of the most powerful public health interventions available to governments worldwide.

The Energy Transition: Where the World Stands in 2025

The global energy transition is real, measurable, and accelerating – though not yet fast enough to meet climate targets. Renewables now supply over 30 percent of global electricity, up from 22 percent in 2015. Solar and wind are cheaper than coal in over 90 percent of the world. Electric vehicle sales reached 18 million units in 2023, representing 18 percent of all new car sales globally. Over 140 countries have net-zero emissions targets enshrined in law or policy. Battery storage capacity is doubling approximately every three years.

At the same time, significant challenges remain. Approximately 80 percent of total global energy – not just electricity, but all energy including heat and transport – still comes from fossil fuels. Around 770 million people worldwide still lack access to electricity, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. Decarbonising heavy industries such as steel, cement, aviation, and shipping remains technically and economically challenging. The International Monetary Fund estimated that global fossil fuel subsidies exceeded 7 trillion dollars in 2022 – a figure that continues to distort market competition and slow the transition. And political will is inconsistent, with some governments actively rolling back climate commitments.

Done fairly and carefully, the energy transition can create millions of jobs, improve public health, enhance energy security, and reduce energy costs over the long term. Done poorly, it risks leaving behind communities and workers who have built their livelihoods around fossil fuel industries. Managing this transition justly – with investment in retraining, economic diversification, and community support – is as important as the technical challenge of replacing fossil fuels with clean alternatives.

What Can You Do? Practical Steps to Support the Energy Transition

At Home

- Install rooftop solar panels if you own your home – payback periods are typically 5 to 8 years now

- Switch to a 100 percent renewable electricity tariff from your energy provider

- Upgrade to an air source heat pump, which is 2 to 3 times more energy-efficient than a gas boiler

- Replace old appliances with the highest energy-efficiency rated models available

- Improve home insulation – can reduce heating energy demand by 30 to 40 percent

- Install smart thermostats and switch all lighting to LED

In Transportation

- Choose an electric or plug-in hybrid vehicle for your next car purchase

- Use public transport, cycle, or walk for short urban journeys wherever possible

- Consider travelling by train rather than flying for journeys under 800 kilometres

- If flying is necessary, choose direct flights – take-off and landing consume the most fuel

As a Consumer and Citizen

- Vote for candidates and policies that prioritise clean energy and climate action

- Move savings and investments into ESG funds that exclude fossil fuel companies

- Reduce consumption of red meat and dairy, which together account for significant agricultural emissions

- Share accurate energy information with friends, family, and on social media – combating misinformation matters

7 Trillion Reasons the Energy Transition is Weirder Than You Think

1. The Decoupling Dilemma

For the better part of a century, economic growth and carbon emissions were joined at the hip: to build a middle class, you had to burn the planet. But we have entered the era of the “Great Decorrelation.” Since the 2015 Paris Agreement, global energy demand has continued its relentless climb-driven by rising living standards across China and the Global South-yet the carbon intensity of that energy is finally, stubbornly falling.On paper, this is a miracle of engineering. In reality, the transition feels like an endless uphill sprint through a thicket of infrastructure bottlenecks and cost shocks. If the sun and wind are free, why is the bill so high? The answer lies in a staggering $7 trillion shadow budget, a misalignment of industrial incentives, and the counter-intuitive physics of building a “clean” world out of heavy metal and concrete.

2. The $7 Trillion “Invisible” Price Tag

When politicians debate fossil fuel subsidies, they usually focus on the “explicit” stuff: direct government checks written to keep pump prices low. According to the 2025 IMF Working Paper, these explicit fiscal supports fell to $725 billion (0.6% of GDP) in 2024 as the energy price spikes of the early 2020s were unwound.But the real story is the “implicit” subsidy-a massive $6.7 trillion social debt. This isn’t a check waiting to be reallocated to wind farms; it’s the unpriced bill for local air pollution, climate damage, and the health costs of premature deaths. This “Invisible Pot” represents 7.1% of global GDP, yet it remains politically untouchable. Why? Because the public lacks confidence in the government’s ability to actually compensate the poor for higher energy costs. As it stands, the system is fundamentally regressive.”Subsidies are intended to protect consumers by keeping prices low, but they come at a substantial cost… and are not well targeted at the poor (mostly benefiting higher income households).” – IMF Working Paper, 2025

3. The CCS “Chicken-and-Egg” Paradox

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) was supposed to be the safety net for heavy industry. Instead, it has become a study in market misalignment. By 2030, Europe is projected to have significantly more CO2 storage capacity than actual capture demand.We are stuck in a “Chicken-and-Egg” trap: industrial emitters won’t sink billions into capture technology without a guaranteed pipe to a storage site, while storage operators won’t build those pipes without firm commitments from emitters. This standoff is worsened by a brutal cost reality check. Early optimism has evaporated, replaced by price tags ranging from €50 to as high as €300 per ton.”In recent years, it has become clear that the total costs associated with capturing, transporting, and storing CO2 are significantly higher than originally expected.” – Gerben Hieminga, Senior Sector Economist, EnergyThere is a light at the end of the tunnel, but it’s distant: DNV projects that economies of scale and standardized designs could drop capex costs by 14% by 2030 and 40% by 2050. Until then, the sector remains a high-stakes waiting game.

4. The Recycling Spoke that Broke

The “circular economy” for batteries is currently eating itself. In North America, we’ve built 450,000 tonnes of recycling capacity, but we only have 180,000 tonnes of available feedstock. We are too good at making batteries last, leaving massive “spoke” facilities like Li-Cycle idling at under 40% utilization.Adding insult to injury, LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate) chemistry is cannibalizing the profit margin. Unlike older cobalt-heavy batteries, LFP cells contain zero cobalt, reducing their “intrinsic value” by 65%. Recyclers are now staring at negative margins. To stop the bleeding, China has drafted rules to force lithium recovery rates for LFP batteries up from 70% to 85%-essentially a regulatory attempt to manufacture value where the market sees none.

5. The Heavy Metal Reality of “Clean” Infrastructure

The most uncomfortable truth for the energy transition is its sheer material intensity. “Green” energy is effectively a massive “carbon capital” expenditure: we must burn carbon today to build the machines that won’t burn it tomorrow.

- Hydropower: The oldest renewable is the most “heavy metal” of them all, requiring the highest amount of concrete per unit of energy generated.

- Wind and Solar: These require an order of magnitude more steel and concrete than the fossil fuel plants they replace.

- The Recycling Gap: While we obsess over battery minerals, there is currently no substantial recycling pathway for the millions of tons of specialized steel and concrete required for renewable power plants.The transition doesn’t eliminate industrial footprints; it front-loads them into mining and cement manufacturing.

6. The “Baseload” Pricing Trap

Solar power is arguably the cheapest energy source in history-until you need it at 9:00 PM. While raw production costs have plummeted to ~ $55/MWh in Europe, that only covers intermittent supply. To build a “reliable baseload” (solar plus 24/7 storage), the price jumps to ~$ 100/MWh, making it more expensive than gas even with an $80/ton carbon price.Consumers aren’t seeing lower bills because of “marginal pricing.” In the UK, natural gas sets the electricity price 98% of the time, even when it provides only 40% of the power. Until the grid can absorb intermittent renewables without relying on gas as the “marginal” filler, the “free” energy of the sun will remain an expensive luxury for the end-user.

The Great Arbitrage

The path forward requires a “Global Carbon Arbitrage.” Currently, the West is spending trillions squeezing the last 5% of efficiency out of European and North American grids. But the data suggests that the cheapest way to save the planet isn’t a new heat pump in Brussels; it’s helping India skip the coal phase. Phasing out just 40% of coal-fired electricity in India would close the global emissions gap more effectively than almost any European domestic policy, and at a fraction of the cost. The EU should authorize at least a 20% offset, channeling finance to these high-impact projects abroad. As we stare down the next decade of decarbonization, we must ask: Are we ready to fund global solutions that actually move the needle, or will we continue to prioritize expensive, local “green” signaling while the shadow of the $7 trillion debt continues to grow?

FAQ:

Is nuclear energy renewable or non-renewable?

Nuclear energy is technically classified as non-renewable because uranium – its primary fuel – is a finite mineral resource that must be mined. However, nuclear power produces virtually no CO2 during operation, placing it among the lowest-carbon electricity sources available. Some scientists argue that advanced thorium reactors or breeder reactors, which produce more fuel than they consume, could blur this classification. For now, most international energy bodies classify nuclear as non-renewable but low-carbon.

Which renewable energy source is the most efficient?

The answer depends on how efficiency is defined. Geothermal energy has the highest capacity factor – meaning it generates electricity almost continuously, around 90 percent of the time. Solar energy has the greatest total potential resource globally. Wind is currently the most cost-efficient renewable in many regions per unit of electricity produced. The best renewable source for any specific location depends on local geography, climate, resource availability, and energy demand patterns.

Can the world run entirely on renewable energy?

Yes – most credible energy models from the IEA, IRENA, and leading academic institutions confirm that a combination of solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal, biomass, tidal, and green hydrogen – supported by grid-scale energy storage – can theoretically meet all of humanity’s energy needs. The challenge is not physical possibility but the speed, cost, political will, and infrastructure investment required to make the transition happen fast enough.

Why do we still use fossil fuels if renewables are cleaner and cheaper?

Primarily because of the enormous existing infrastructure built around fossil fuels over the past 150 years, the intermittency challenges of solar and wind, energy storage limitations at scale, political resistance from fossil fuel industries and the communities dependent on them, and the massive direct and indirect subsidies – estimated at $7 trillion globally in 2022 – that continue to keep fossil fuels artificially competitive. All of these barriers are real, but all are being actively eroded by falling technology costs and increasingly determined policy action.

What country uses the highest percentage of renewable energy?

Iceland generates nearly 100 percent of its electricity and approximately 90 percent of its total primary energy from renewables – almost entirely geothermal and hydropower. Norway generates around 98 percent of its electricity from hydropower. Costa Rica regularly achieves 99 percent or more renewable electricity throughout the year. Paraguay generates virtually all of its electricity from the Itaipu hydroelectric dam. Among large industrialised nations, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada have made the most substantial and rapid renewable transitions.

What are the biggest disadvantages of renewable energy?

The main challenges are intermittency (solar and wind do not produce power around the clock), the current cost and capacity limitations of grid-scale battery storage, the high upfront capital cost of large-scale renewable infrastructure, land use requirements for solar farms and wind farms, and the environmental and supply chain concerns around manufacturing and end-of-life disposal of solar panels, wind turbine blades, and batteries. All of these challenges are being actively addressed through research, engineering innovation, and policy development, and progress is faster than most analysts anticipated even five years ago.

Conclusion

The energy we choose to generate and consume is not merely a technical or economic decision – it is a deeply consequential civilisational choice. The type of fuel burned in a power station on the other side of the world contributes to the same atmosphere that blankets every nation, every ecosystem, and every living being on Earth. There is no such thing as a purely local energy decision.

The top 10 renewable sources explored in this guide – from the extraordinary abundance of solar and wind to the emerging promise of green hydrogen, tidal energy, and ocean thermal systems – collectively represent a fully viable path to a world powered by clean, affordable, and effectively inexhaustible resources. The top 10 non-renewable sources – coal, oil, natural gas, and their variants – represent the inherited energy system of the Industrial Age, one that brought immense economic development but also accumulated environmental debt that is now coming due.

The encouraging reality is that economic gravity has shifted decisively toward clean energy. Solar and wind are now the cheapest way to generate electricity in most of the world. The energy transition is not a question of whether it will happen – it is already happening. The question is whether it happens fast enough, equitably enough, and with enough political courage to prevent the worst consequences of climate change.

Understanding where energy comes from – and what each source costs the planet – is the essential starting point. What we all do with that understanding, in our homes, our communities, and our democracies, is where the real story begins.